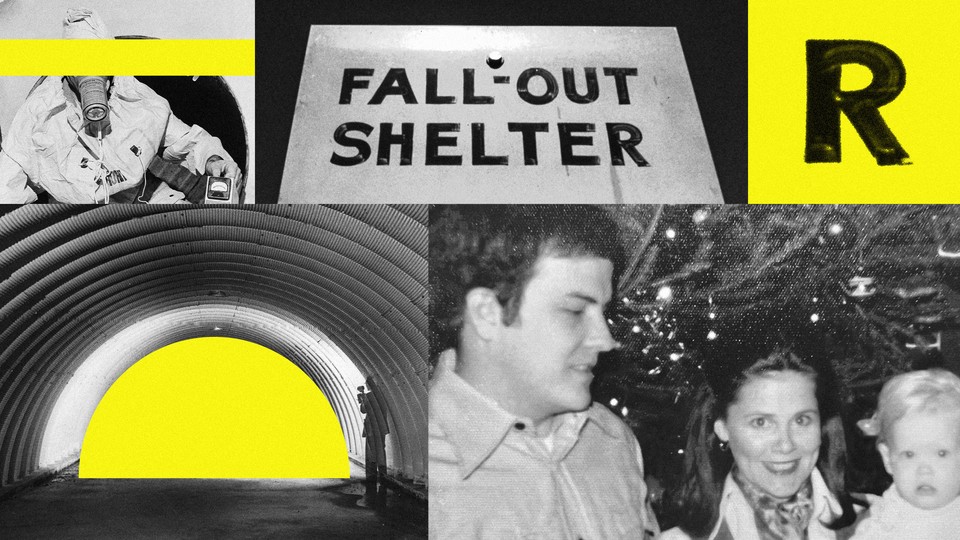

The Most Haunting Truth of Parenthood

What my father learned working in a nuclear bomb shelter is what every parent knows deep down: We can’t protect the ones we love forever.

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

Do we ever really understand our parents? Certainly not when we’re children. If we’re lucky, we begin to understand them later. We might one day realize, for example, that they carried burdens we couldn’t see. Sometimes I wonder if I might have learned something important about what was to come in adulthood had I been paying closer attention when I was little, but no, I couldn’t have related then. It is only in recent years, when the most maddening, haunting fact of parenting has become clear to me, that I’ve realized my mom and dad must have known it all along: What parents want most of all—to keep our children safe forever––is the one thing that’s absolutely impossible.

I had a revelation along these lines after a phone call from my father on a Saturday afternoon a few years ago. I was making lunch in my kitchen for myself, my husband, and our adolescent son and daughter. We were in the phase of life where our children were beginning to turn into adults, time ticking by as one teenager prepared to leave the nest after the other. As their lives grew busier with each passing year, I saw less and less of them. They were moving further out from under my wing, and I felt proud of them at the same time that I had a primal urge to swallow them whole, absorb them right back into my body.

As I sliced cabbage into ribbons for slaw, Dad told me about my mother’s garden project and a sci-fi movie he wanted to go see. Just as I was about to say goodbye, he asked if I’d heard about a new book by Garrett M. Graff. “It’s called Raven Rock.”

I had indeed heard some buzz about the book. It was the true story of the secret underground bunkers the U.S. maintained for decades starting in the 20th century, intended to house and protect high-ranking government officials in the event of a nuclear attack. The book’s subtitle says it all: “The Story of the U.S. Government’s Secret Plan to Save Itself—While the Rest of Us Die.”

My dad’s bedside table is typically stacked with paperback novels about what the world would be like if the planet were ruled by Russian robots or if America had been taken over by zombies. So when he asked if I’d order him this book about hidden subterranean government control centers, I said, “Sure, Dad. Sounds right up your alley.”

“It reminds me of when I worked there,” he replied.

“Worked where?”

“There.”

“... there?”

“Yeah, at Site R—at Raven Rock.”

Oh, of course. There. The secret underground bunker he had never mentioned to me once in my life.

You think you know somebody.

I reviewed what I knew—or what I thought I knew—about my father’s career.

During Vietnam, my father was in medical school as well as the Army Reserve. While on a rotation in Hawaii, where he and my mother lived briefly before I was born, his responsibilities included treating soldiers and their families; across the ocean in the battle-bloody jungle, many of his peers were fighting. Born at the dawn of the Cold War, educated in the “duck and cover” years of hiding under classroom desks during bomb drills, he had never imagined war as some kind of vague, far-off possibility. He knew the truth, that whether it is happening here at home or on a continent far enough away to seem “foreign” to those who wish to distance themselves from it, conflict is raging somewhere at any given time. War is always.

Dad stayed in the army for a few more years after he and my mom left Hawaii, while he continued his specialized medical training. He went on to become a renowned surgeon, moving our family from city to city after I was born, dedicating his life to intellectual challenge and scientific innovation. In the operating room, he used cutting-edge equipment to restore people’s hearing and relieve patients of pain. He often traveled the world to share expertise in his highly specialized field of neurotology. When he couldn’t find the exact tools he wanted for performing microsurgery inside people’s ears, he invented them. He often prowled Home Depot for tidbits of metal and plastic, screws and hinges, then put them together and took them apart again in his basement workshop, creating prototypes for things he’d like to make on a smaller scale.

Growing up, I knew we had lived near the nation’s capital during the Bicentennial celebration of 1976, not because I remembered it—I was barely more than a baby—but because I’d seen pictures of my toddler self walking around the parade grounds waving a little American flag.

Is it really possible that I had no idea what my dad had been doing when I was young?

It wasn’t as if our family stopped doing regular things while my father was doing this not-at-all-regular job. I went to nursery school. We planted a garden, and I stepped on a bee. We found a baby bird and tried to feed it in a shoe box and buried it when it died. I found a roll of cinnamon breath mints and ate the whole thing and for one long afternoon thought I could breathe fire. These are the things I remember.

The extraordinary doesn’t wipe out the ordinary. People get married in wartime. Babies are born during pandemics. My mom drew water for my bath and flung wet clothes into the dryer and taught me to tie my shoes while my father did test runs for the end of the world.

After my dad casually dropped this news, I pressed for some details. “But what exactly were you doing when we lived outside D.C.?”

He explained that he had been a general medical officer stationed at the Fort Ritchie health clinic. He and some other officers were assigned the job of going to Camp David for routine tasks such as giving flu shots to the company of Marines stationed there. My dad was not the physician to President Gerald Ford—he was far too young then—but he was at Camp David sometimes when Ford visited.

“What about Raven Rock?” I asked.

“We called it ‘Site R.’ My army corpsman, George, and I would go over fairly frequently to check on things. Sometimes we’d take the Oldsmobile ambulance to the helipad when the secretary of defense came up. Good thing the helicopter never crashed.” He chuckled.

“But the thing with the drills, what did you practice?”

“We practiced the plan.”

“I know, but … what was the plan?”

“Well, the plan was, George and I would get over there fast to open up the hospital and hope the rest of the team would get there soon. I suppose we were there to keep people alive—the people who would run the country and the military in the event of a disaster.”

“Oh my God, Dad. How did you feel about all that?”

“Dazzled, at first! Then kind of bored. We were never put to use, thank goodness.”

I asked if the existential weight of it ever got to him. He handed the phone to my mom.

“Every now and then … off he would go into the cave, and there we would sit at home,” she said. “I didn’t feel like we were in any real danger of having a nuclear attack—it was just drills. But every now and then I would look at you and think, Well, what are we? Lunch meat?”

Graff’s book—which I bought and read after this conversation—includes a scene in which President Ford’s press secretary, Ron Nessen, tours one of the secret bunkers in 1976:

“The last line of his evacuation instructions had been clear: ‘There are no provisions for families at the relocation or assembly sites.’ Would he have really abandoned all of his family in the country’s hour of need?”

What a question.

Was it strange for my father? To descend below the surface of the Earth, to go through the motions of what he would do if the president were rushed into an underground hospital while, above ground, human life ceased? Did he walk out of our house in the morning as I ate my toaster waffle imagining that if this thing he practiced ever came to be, he would one day walk out of this house and never walk in again? That my mother, our house, my baby brother, and I would all be blasted into hot dust?

I wondered whether my dad ever thought the whole exercise was pointless. If humanity has nuked itself into oblivion and there’s no safe world left to return to above ground, it’s not like hunkering down in a man-made fallout fortress will be any more effective than ducking and covering beneath a desk. The end still awaits whenever they open up that chamber, meaning that no one is really saved, only temporarily protected. Getting ready for an atomic bomb to fall doesn’t predict or influence whether the bomb will fall. It’s all pretend, just busywork, isn’t it?

What is a bomb shelter but either practice for something that will never happen or a postponement of the inevitable?

When I was in college—oh, this is one of my favorite Dad stories—he used to send the most bizarre care packages. Other kids received Tupperware containers full of homemade brownies, maybe a pair of mittens or an envelope of cash if they were lucky. That’s what I got, too, if my mom was packing the box. But the packages from my dad almost never included a note and always contained canned food.

It was a strange delight, toting those boxes across campus from the post office, knowing from their heft that they were filled with nonperishable items for a pantry I didn’t have. It became a joke between my roommate and me. What would my dad send next––Vienna sausages, canned pineapple? Did he think I didn’t have access to food at school? That my dorm-mates and I might be building some sort of survival stockpile? We giggled every time one arrived—honest to God, we sometimes joked, “Here we go, another bomb-shelter box”—and stacked the cans under our beds. We ate the food, but not as fast as it accumulated.

How strange, I thought then, but also how sweet. My quirky dad, showing love via canned goods, of all things.

I am about 20 years older today than my father was when he worked in the bunker. My son left for college last fall. In two years, my daughter will leave home as well. I realize now that their leaving does not conclude my parenting, at least not in my heart. I will never stop worrying about them. I feel as if I’ve been walking around for decades now wearing an invisible explosive vest. The longer I live, the more I love, the larger this combustible bundle grows, the more I am in awe of my good fortune—and also aware that it could all blow up in an instant, flipping me head over heels into the air, vaporizing everything. Sometimes it almost knocks me down, this combination of gratitude and fear. I often feel like the universe entrusted me with so much more than I could possibly keep safe.

I didn’t understand when I opened those care packages in college. I do now.

Although the worst-case scenario my dad prepared for didn’t come to pass then, other horrors have over the years––and still do. My heart breaks for parents in Ukraine today, putting their children on trains with strangers to travel over a border to safety, watching their teenagers arm themselves to enter combat for which they haven’t been adequately trained.

Whether in a hypothetical nuclear attack, in the brutal reality of ongoing war, or in the simple, mundane truth of being a living soul trapped in a mortal human body, it is a fact: We cannot really save anyone. Not permanently. The safeguards we set up all fall away. In the best-case scenario, our babies grow up healthy and strong under our watch, then leave to set out on their own. Worst case, our attempts to protect our loved ones fail, and they are felled by something we could not stop. Knowing this––as my parents surely did during the bunker years, and as I do now as a mother––could drive us mad.

What do we do, then, if we cannot stop time or prevent every loss?

We carry on with ordinary acts of everyday caretaking. I cannot shield my beloveds forever, but I can make them lunch today. I can teach a teenager to drive. I can take someone to a doctor appointment, fix the big crack in the ceiling when it begins to leak, and tuck everyone in at night until I can’t anymore. I can do small acts of nurturing that stand in for big, impossible acts of permanent protection, because the closest thing to lasting shelter we can offer one another is love, as deep and wide and in as many forms as we can give it.

We take care of who we can and what we can.

The amount of time that elapsed between my 2-year-old self toddling along the National Mall waving a flag and my 18-year-old self moving into a dorm feels vast in my memory. But I understand now that those years didn’t feel long to my father. Between the days when the siren called him down into the bunker and the days when he started packing boxes full of shelf-stable food to send to his baby, hardly any time passed at all.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.