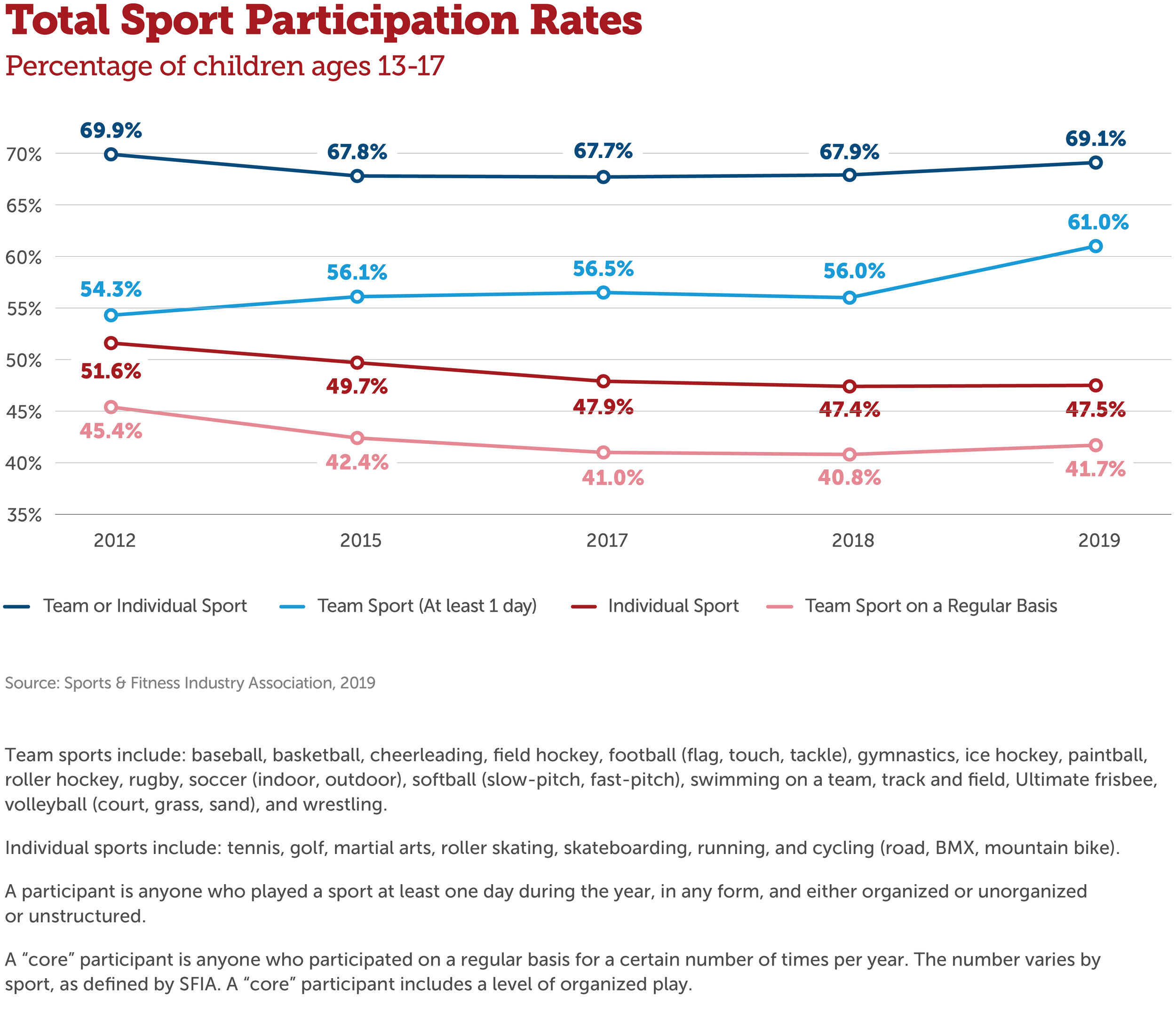

While large numbers of adolescents did not play sports, participation was increasing in 2019 for youth ages 13-17 prior to the pandemic in all forms of sports. “As we see the industry expand in sheer numbers, kids are taking advantage of it,” said Karissa Niehoff, executive director of the National Federation of State High School Associations. “I don’t think kids drop out because they don’t want to play. I think the majority drop out either because of a lack of access to opportunity or it’s not fun. They burn out.”

Watch “A Historic Challenge for Schools” panel at Project Play Summit here.

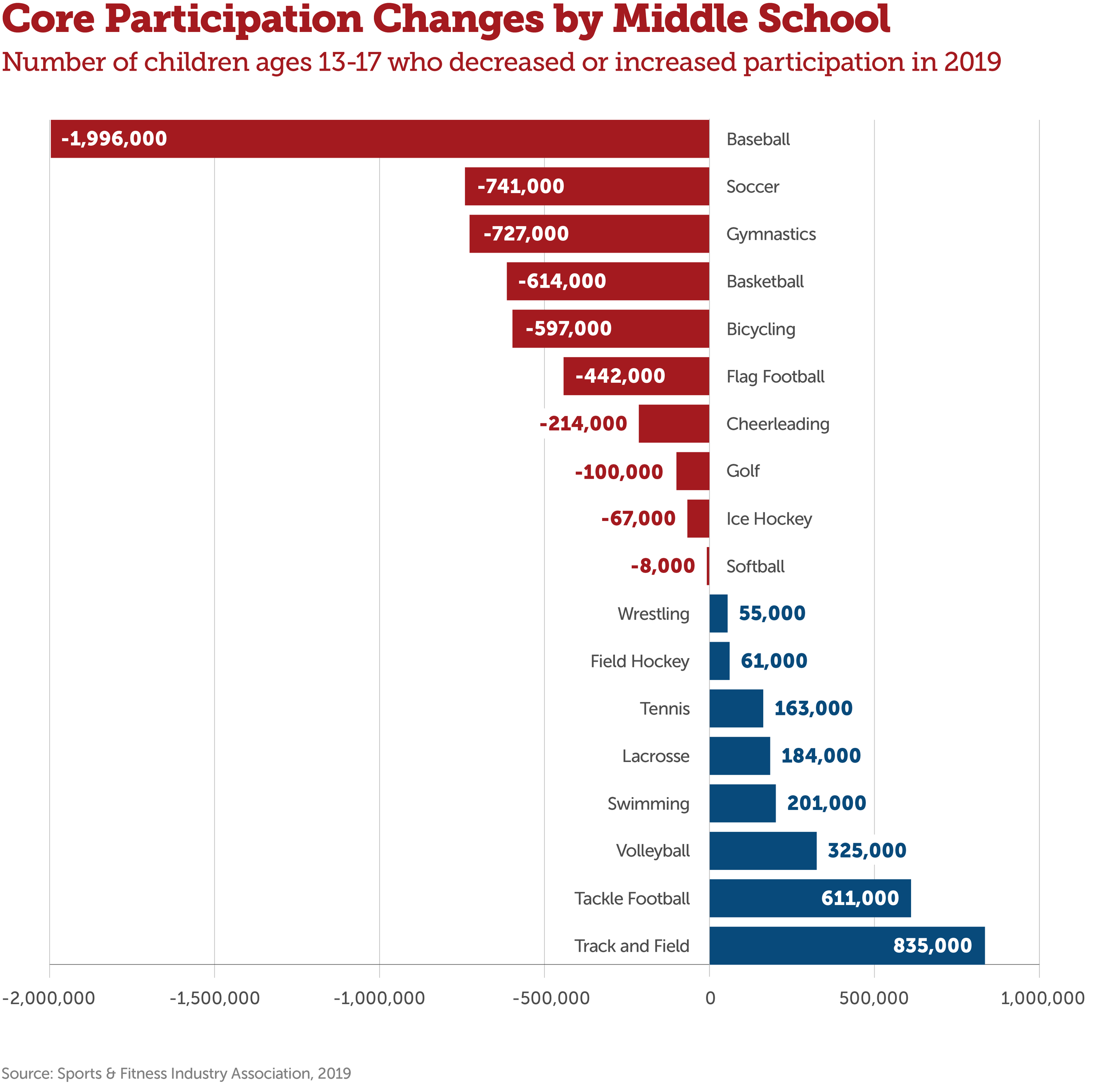

The COVID-19 shutdown will become an inflection point for participation and it’s difficult yet to sort out what that will look like. In 2019, many sports were experiencing gains among youth ages 13-17. Softball (12%), lacrosse (8%), field hockey (8%), volleyball (8%) enjoyed the highest rate of participation growth. Tennis (5%) and cheerleading (4%) had the steepest declines. Might an individual sport like tennis gain future popularity because it’s a socially distant sport?

Worth noting: Although football is America’s most popular spectator sport, the number of football participants at ages 13-17 (1.46 million) still trails basketball (3.44 million), baseball (2.18 million) and soccer (1.48 million) and is only slightly ahead of tennis (1.41 million). Similar results were found in an Aspen Institute/Utah State University survey in 2020 during the pandemic, when youth sports parents were asked what they would consider their child’s primary sport. Parents with kids ages 6-18 identified basketball (22%), baseball (15%), soccer (14%), tackle football (8%), and gymnastics (6%) as the most popular.

Some positive news for football: High school participation shrunk again in 2019, but at a much slower rate than in previous years, according to the National Federation of State High School Associations. The organization’s annual survey showed 2,489 fewer football players in 2019, marking the 10th time in 11 years that participation has dropped. But the 2019 drop was much less than 2016-18 (23,311, 20,540 and 30,829). “I think there’s a little bit of restored trust in the quality of attention to risk minimization, coach education and parent education,” Niehoff said.

Even before the pandemic, the youth sports ecosystem lost almost 3 million kids during the transition from elementary to middle school ages. No sport lost more kids by middle school than baseball, with almost 2 million fewer participants for ages 13-17 than ages 6-12. The challenge of stemming those losses is structural: Little League and other forms of community-based play are dominant through age 13, at which point the competitive pitching level increases, players transition to larger fields and travel teams come to dominate the landscape.

Some sports are intentionally formatted as physically better suited for younger kids (gymnastics) while some are designed more for older youth (tackle football). Individual sports such as tennis, swimming and track and field gained participants by middle school. As youth sports organizations and schools likely experience participation declines due to COVID-19 and the economy, could some sports dramatically change their playing models at earlier ages to get kids engaged sooner instead of waiting until the school setting?

Sports & Fitness Industry Association CEO Tom Cove offers a cautionary tale on this question. A decade ago, he said, hockey and lacrosse regularly experienced participation numbers increase in the later years for youth because most communities didn’t offer those sports at younger ages. Hockey and lacrosse were viewed as interesting alternatives for kids as they got older. Now the growth is stymied at older ages.

“When you promote lacrosse and hockey at a young age, you get them good at stickhandling much earlier, so 12-year-olds who go out for the junior high or club team for the first time aren’t good enough, and they quit and walk away,” Cove said. “That’s where you see it trending – the growth of going younger really hurts the growth at later ages.”

Learn about Project Play’s "Reimagining School Sports" initiative here.

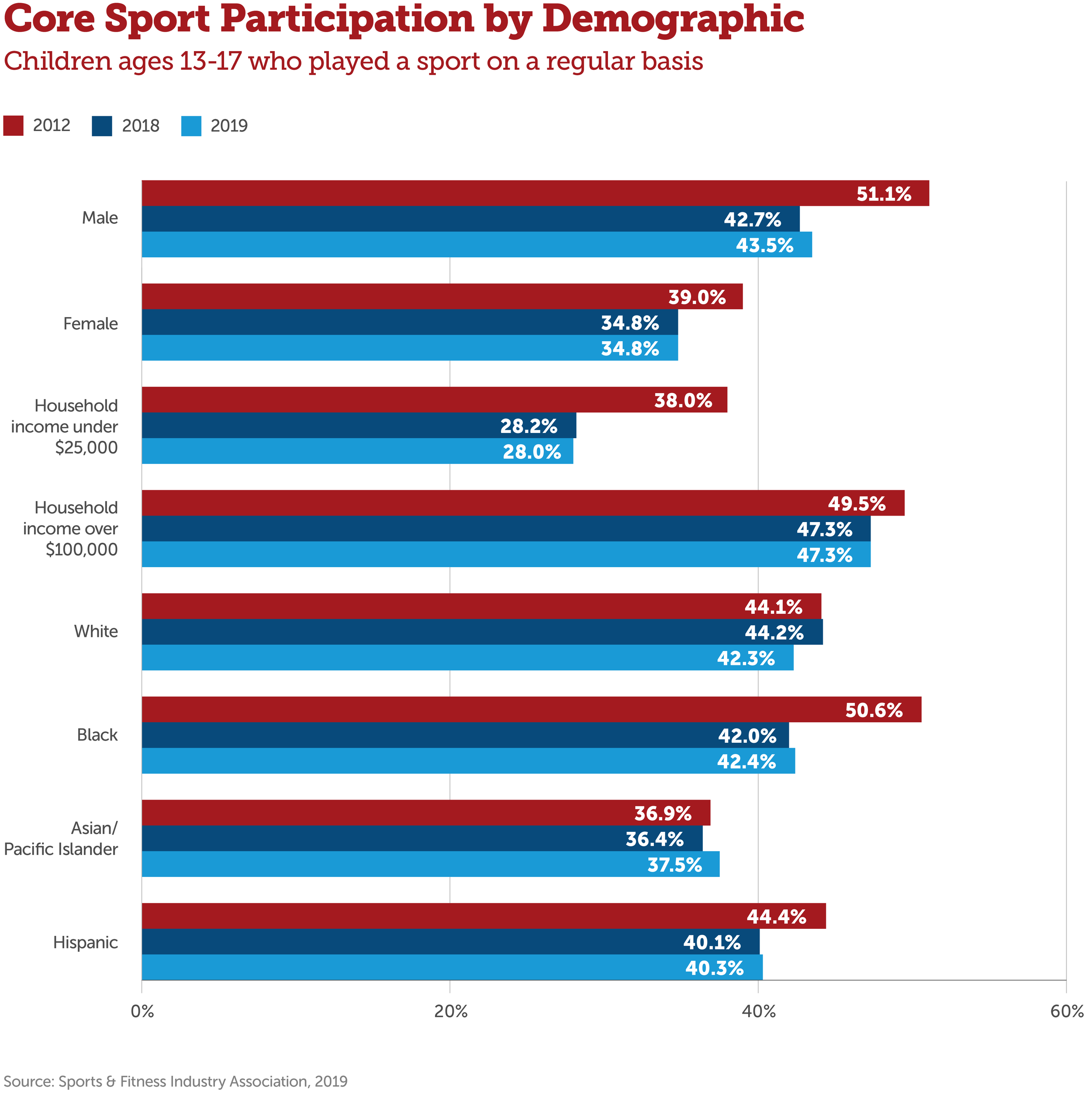

Unlike with kids ages 6-12, sports participation by race and ethnicity was fairly balanced among ages 13-17 in 2019: Blacks (42%), Whites (42%), Hispanics (40%), Asians/Pacific Islanders (38%). However, the trend line is most concerning with youth who are Black, whose rates of participation have fallen the farthest since 2012, when half of them played sports.

Participation increased for both males and females in the older age group, but the gap widened. Males played sports more regularly than females by 6.4 percentage points at ages 6-12 and by 8.7 percentage points at ages 13-17.

“There are many complex and intersectional reasons that help explain the growing (gender) gap – girls’ choices, family circumstances, changing interests, societal stereotypes, gender biases and community offering,” said Nicole LaVoi, co-director of the Tucker Center for Research on Girls & Women in Sport. “I think societal stereotypes are changing, but stereotypes about the female body, what it means to be feminine, and what it means to be an athlete are sometimes in opposition of what it means to be a female athlete.”

Only 28% of youth 13-17 living in homes with an income under $25,000 consistently played sports, compared to 47% in homes over $100,000. COVID-19 is already widening the participation gap due to family finances and safety concerns. (See data in Pandemic Trends section).

Read "Why the time is now to coach mental health in youth sports" here.

18%

Youth who engaged in no sport activity in 2019

For the fifth straight year, older youth were less physically inactive. The 2019 rate still leaves room for improvement – 18% of youth engaged in no sport activity at all during the entire year. But it’s gradual progress.

Changing the narrative about the role of sport has likely contributed to this decrease, said Renata Simril, LA84 Foundation CEO. “When you talk about it and make it a priority, it helps,” she said. “I’d like to think anecdotally that campaigns like we do, and Project Play did with #DontRetireKid, and BOKS does with exercise programs before and after school, that these campaigns matter. Now we have to also bring awareness to legislative policymakers. There’s still a lot of work to do when you think about the economic divide and communities of color in health, as we’re seeing with COVID cases in Black and Brown communities.”

Read "For kids with disabilities, sports will return much more cautiously" here.